Researchers at Illinois Institute of Technology and Loyola University have discovered new clues in the 100-year-old mystery of the Frank-Starling law of the heart: What makes the heart contract more strongly at longer lengths given the same level of calcium activation?

Writing in the February 8 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), Biology professor Thomas Irving of Illinois Tech and Pieter de Tombe of the Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine demonstrated that the muscle protein titin plays a key role in the Frank-Starling mechanism. The findings will enable researchers to develop more realistic models of cardiac function and improve their understanding of cardiac dysfunction in heart failure.

First proposed in 1914, Frank-Starling refers to the physiological observation that the greater the volume of blood that enters the heart during diastole – or normal heart dilation, when chambers fill with blood – the higher the blood pressure when more blood is sent out of the chambers during systole, when the ventricles contract. Although researchers have known of the phenomenon for a long time, they have not known how it works. They knew only that the Frank-Starling mechanism does not properly work in people with heart failure; the heart does not pump enough blood.

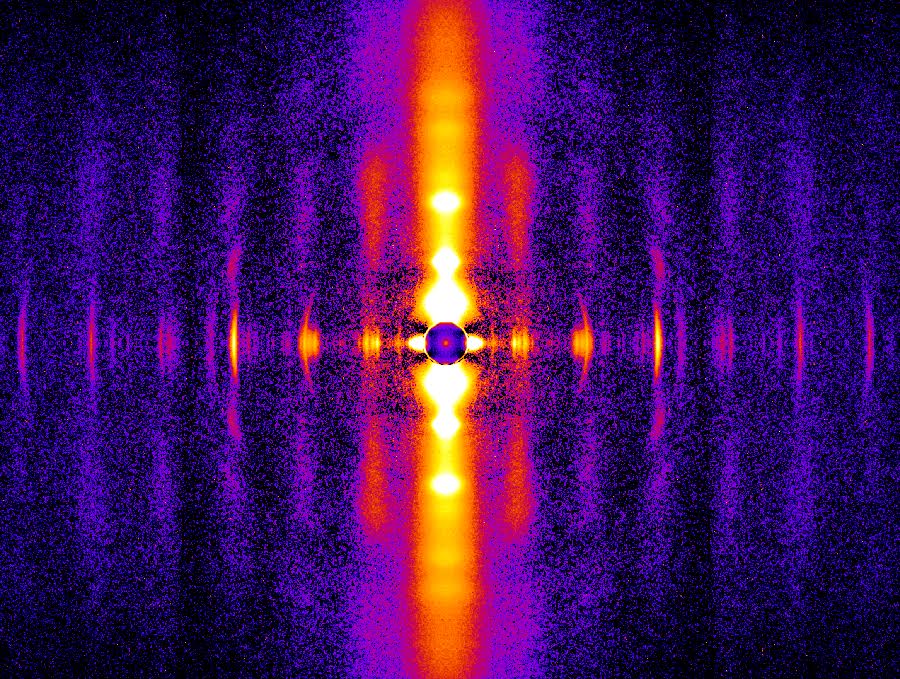

To explore the mechanism, Irving, De Tombe, and their team examined live rat heart muscle at the millionth of a millimeter (nanoscale) level, using small angle X-ray diffraction techniques at Illinois Tech’s Biophysics Collaborative Access Team (BioCAT) beamline 18ID at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. BioCAT is considered to be one of the best facilities in the world for muscle diffraction studies.

A heart muscle contracts because of interactions between bundles of proteins called myosin assembled into so-called thick filaments with the protein actin assembled into so-called thin filaments. When a nerve impulse stimulates the muscle, calcium is released from stores that can move into the thick and thin filaments. Portions of the myosin muscle then interact with the thin filaments, causing muscle to shorten and generate force. Another important protein, titin, acts like a rubber band that stores energy when muscle is stretched and releases it when it shortens. Earlier researchers proposed that alterations in the titin molecules were connected to heart failure. But they did not know why muscle generates more force for the same amount of calcium when muscle is stretched to longer lengths.

Illinois Tech and Loyola researchers found that normal titin molecules pulling on the thick filaments caused changes in thick filament structure that were simultaneously accompanied by changes in the thin filament structure, and these thin filament changes were those normally associated with allowing the muscle to contract. These structural changes were absent in muscles that had longer titin molecules that did not pull as hard on the thick filaments. What tells the proteins that the muscle has been stretched as it would be at larger diastolic volumes, is how much the titin pulls on the thick and thin filaments. This provides an important part of the long-sought explanation for the increased force at longer muscle length that underlies the Frank-Starling mechanism.

Diffraction patterns from beating rat heart muscles allow study of thick and thin filament structure.

“This is a significant step forward in our understanding of the workings of the heart,” said Irving. “Although we still don’t know what the connections are chemically that transmit titin’s force from the thick filaments to the thin filaments, we now know that there must be such connections. The next step is to identify this missing link.”